Your essay “Weapons of Choice” explores the array of tools you use, from brushes and pens to Sumi ink. Has your artistic process been predominantly analog throughout your career?

“Creating graphic novels is a different ball game from comics,” Pope said. “It’s akin to crafting a novel, it may take years, and you work under a contract. No one gets to see the work, so it can be quite frustrating.”

Absolutely. One current challenge is the ease with which one can download an app or acquire an iPad Pro to start drawing. The learning curve may be quicker in some respects, and you can rectify, edit, and change aspects you don’t like. However, it leads to an endless cycle of drawing.

This marks the start of a series I’ve been planning for some time. The gallery exhibition would be the next step. I have another project announcement planned for later this summer.

Luckily, the period of little rain is nearing its conclusion. An exhibition showcasing Pope’s career has just opened at the Philippe Labaune Gallery in New York. A revised version of his art book, now titled “PulpHope2: The Art of Paul Pope,” was released in March. Additionally, the first volume of Pope’s self-published sci-fi series, “THB,” is scheduled for release in the fall.

“My focus is not on someone randomly creating an image based on one of my drawings, but on real concerns like killer robots, surveillance, and drones,” he commented.

Do you consider ink on paper inherently superior, or is it simply your preferred method?

You have an upcoming gallery exhibition coordinated with the release of the second volume of your art book, “PulpHope.” Can you describe the genesis of these projects?

My concerns are less about random individuals reproducing my artwork using AI and more about the implications of autonomous killer robots, surveillance, and drones. This poses a more serious concern because without careful consideration of the consequences, we might be approaching a tipping point indicative of hasty technological progress.

The issue has sparked debates among cartoonists regarding authorship and copyright protection. I recently discussed this very topic with Frank Miller. If I were to request AI to create “Lady Godiva, nude on a horse, as envisioned by Frank Miller,” it could produce the content in under 30 seconds. Some might claim ownership of that output. However, AI does not create art from the same origins as humans, drawing from identity, personal history, and emotional depth.

You mentioned using AI for research and non-creative purposes. What are your thoughts on AI in the creative process?

The following conversation has been edited for brevity and clarity.

I would say mostly. I introduced Photoshop relatively late, around 2003, for coloring and adding textures.

One aspect I truly appreciate in analog art is its demanding nature. I received a crucial piece of advice early on: the first 1,000 brush ink drawings you make will likely be subpar, and you just have to push through that initial phase. It was humbling, but over time, I gained mastery over the tool, allowing me to express my ideas more accurately.

The contrast is significant in Pope’s case, given his preference for traditional tools like brushes and ink over digital methods. Nevertheless, he expressed openness to utilizing AI, which he currently uses for research purposes.

You seem skeptical about AI‘s creative capabilities, but do not disregard its usefulness where appropriate.

- Despite this, I have faith in human innovation and believe in our unique creative abilities. Machine intelligence may mimic human endeavors, but it lacks the essence of human invention

- an area where true innovation thrives.

When interacting with younger artists, do you believe there’s still room for them to engage in analog art?

Pope is resurfacing at a crucial moment for the comic industry and creativity in general. Publishers and writers are taking legal action against AI companies while generative AI tools are gaining popularity by imitating established artists. He even suggested that it’s “entirely plausible” for comic illustrators to be replaced by AI in the near future.

It seems inevitable. The cat is out of the bag. The focus now needs to be on providing artists with a diverse range of tools to choose from.

Around 2010, I developed carpal tunnel syndrome, which led me to reduce my use of digital tools, although I still utilize them. I use Photoshop almost daily. However, the foundation of my work lies in the traditional comic purism of pen and paper.

Additionally, I feel obliged to artists like Alex Toth and Steve Ditko, who generously shared their knowledge with me. Moebius and Frank Miller, whom I knew, all worked with traditional analog art. I aspire to continue that tradition.

Indeed, AI is just a tool.

AI has the potential to remix existing programmed data, which could include my work. While the resulting art may not resemble mine, advancements are continuously being made. From a futuristic perspective, the pressing concerns revolve around killer machines, surveillance, and rapid technological advancements devoid of ethical contemplation.

Honestly, I don’t view it as superior. Any effective tool can work well. Moebius once said there were times he sketched with coffee grounds or even a fork.

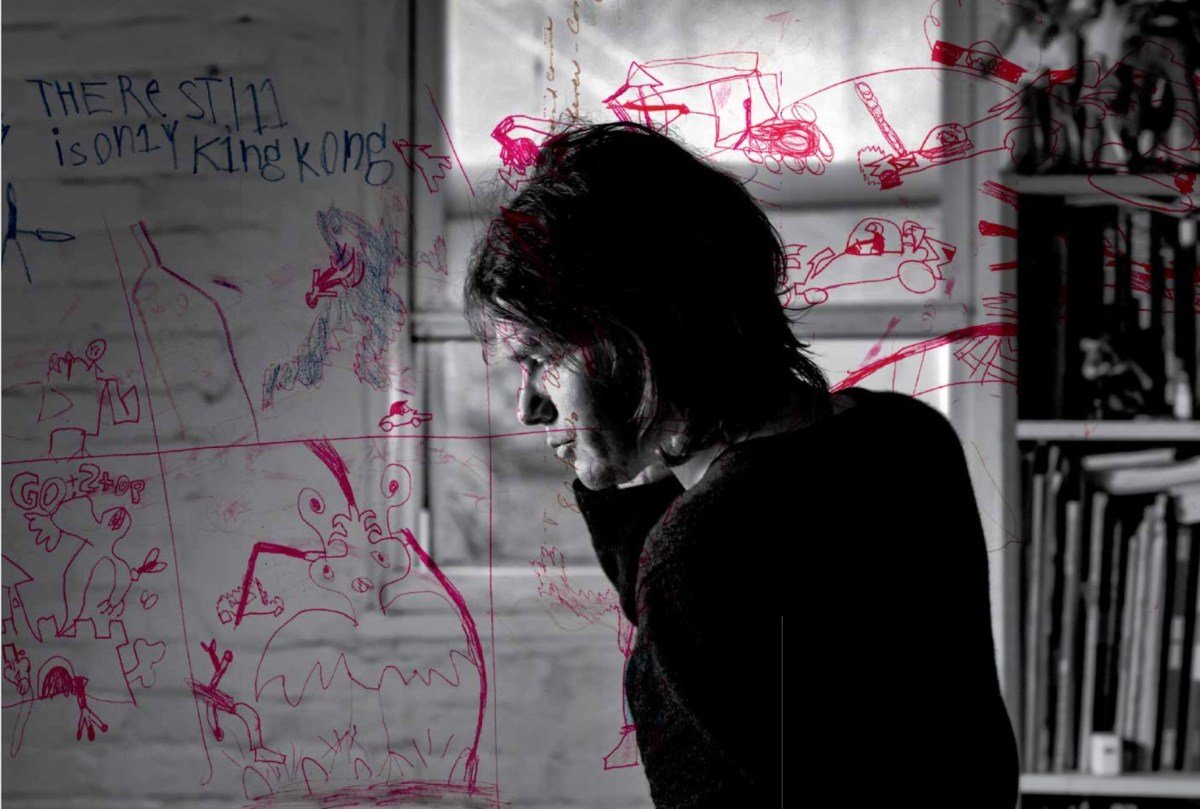

It has been more than a decade since Pope’s last major comic project, and during a Zoom chat with TechCrunch, he shared his frustrations over the years. At one point, he showed a large batch of drawings and mentioned that none of it has been seen by the public yet.

- I think it’s a mixture of both. I’ve mentioned this before

- at a certain stage, an artist must curate their own work. Jack Kirby famously said, “The only thing that matters is your top 10% of work. The rest brings you to that 10%.”

- Currently, I was captivated by a remarkable exhibition on 23rd Street at Poster House in New York that chronicles twentieth-century poster design. The exhibit delves into the portrayal of the atom bomb across various contexts in poster art. The “Atoms for Peace” movement, which advocates for atomic energy while opposing war, resonated with me, much like my view on AI

- “AI for peace.”

The upcoming release of your collection of “THB” comics this fall marks another strategic step in reshaping your artistic persona. Can we expect “Battling Boy 2” or any other upcoming moves from you?

In my case, I’ve created numerous variant covers and delved into various projects beyond comics, such as screen prints or collaborations with the fashion industry, often challenging to access. I found it intriguing to present a chronological exploration of an artist’s life, primarily focusing on comics with many unseen or hard-to-find pieces.

I sometimes use AI to structure stories. However, I see it more as a consultant than a creator. My nephew describes AI as a sociopathic personal assistant unfazed by dishonesty. At times, I’ve consulted AI about my own publications, a process that has shown some discrepancies in accuracy.

Boom Studios reached out to me, I believe it was late 2023, expressing interest in a potential collaboration [through their boutique imprint Archaia]. After some negotiation, I joined as the art director. We worked together for about nine months in 2024, compiling the book. Interestingly, I know Philippe Labaune through mutual connections, and he suggested showcasing not only work from the book but also a retrospective of my career. It turned into something quite remarkable.

What is your view on the increasing digitalization of comic art creation?

Absolutely. Interestingly, we had “Battling Boy 2” initially planned before the release of “THB.” Due to a reorganization within my publisher’s parent company, Macmillan, we decided to reshuffle the lineup. “THB” is now set for release, bringing new energy and effectively reigniting my creative spark.

Do you contemplate the trajectory of your career and how it fits together, or do you mostly look ahead to the future?

Indeed, I rely on AI for various tasks, but I limit its usage to non-creative pursuits. For example, I recently wrote an essay on one of my favorite cartoonists, Attilio Micheluzzi. Fantagraphics is currently releasing compilations of his work, and I contributed to the introduction of the second book. AI proved incredibly helpful in uncovering obscure personal details about Micheluzzi that would have otherwise been difficult to find manually.

- These are all part of what Pope describes as “a series of strategic moves” aimed at “reintroducing” and

- reluctantly, he admitted

- “rebranding” himself.

My legal advisor even suggested that Marvel Comics might potentially replace artists with AI in the coming years. If storyboarding for films can be AI-driven, comic creators might follow suit. Almost every profession could face the threat of automation.

I have many friends, some working on highly acclaimed mainstream projects, who have transitioned to digital techniques for their various advantages. However, that shift doesn’t resonate with me. One crucial aspect is that I sell original art, and with a digital file, you can reproduce prints, but the essence of drawing is lost. It’s merely binary code.

The process of creating graphic novels differs significantly from making comics. It involves crafting a novel, a lengthy undertaking that can last for years and is usually done under a contract. Much of this work remains unseen, which can be quite frustrating. The various projects on this stack before me are all works in progress, none of which have been published yet. I viewed this as a great opportunity to reintroduce my work or, as I prefer, refresh my image.

Paul Pope has created some incredibly stunning comics in the twenty-first century. From “Batman: Year 100,” where Batman confronts a dystopian surveillance state, to “Battling Boy,” featuring a young god proving his bravery by battling massive monsters.