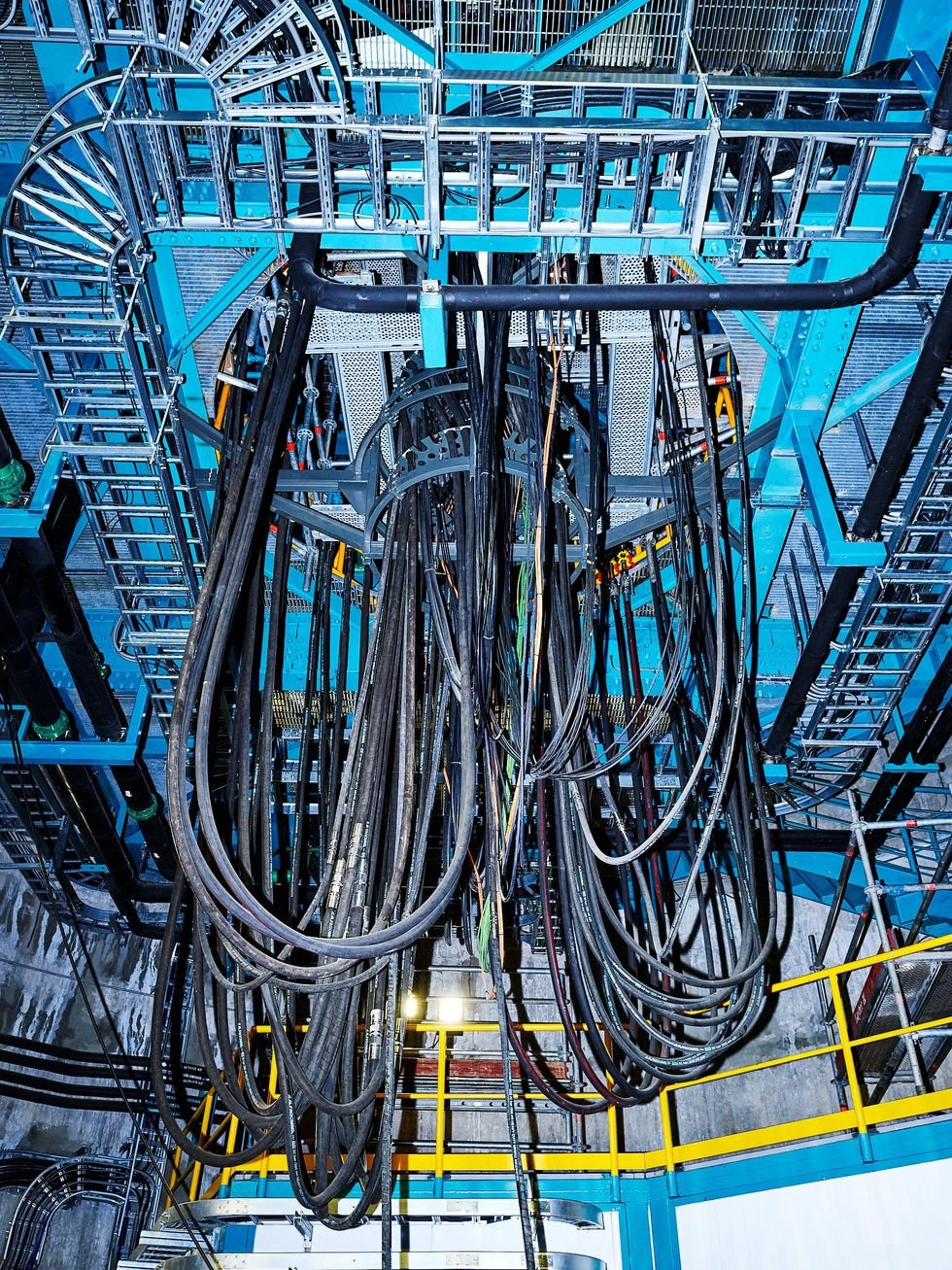

The data management system is as crucial to Rubin’s operations as the telescope itself. Unlike most telescopes focusing on specific observations shared with only select astronomers, Rubin will make its data widely available within days, fostering a new approach to astronomy. “We’ve essentially committed to capturing every image of everything everyone ever wanted to see,” explains Kevin Reil, Rubin Observatory scientist. “If data is collectible, we aim to acquire it. If you’re an astronomer and desire an image, within days, we’ll have it ready for you. Delivering on this scale presents a monumental challenge.”

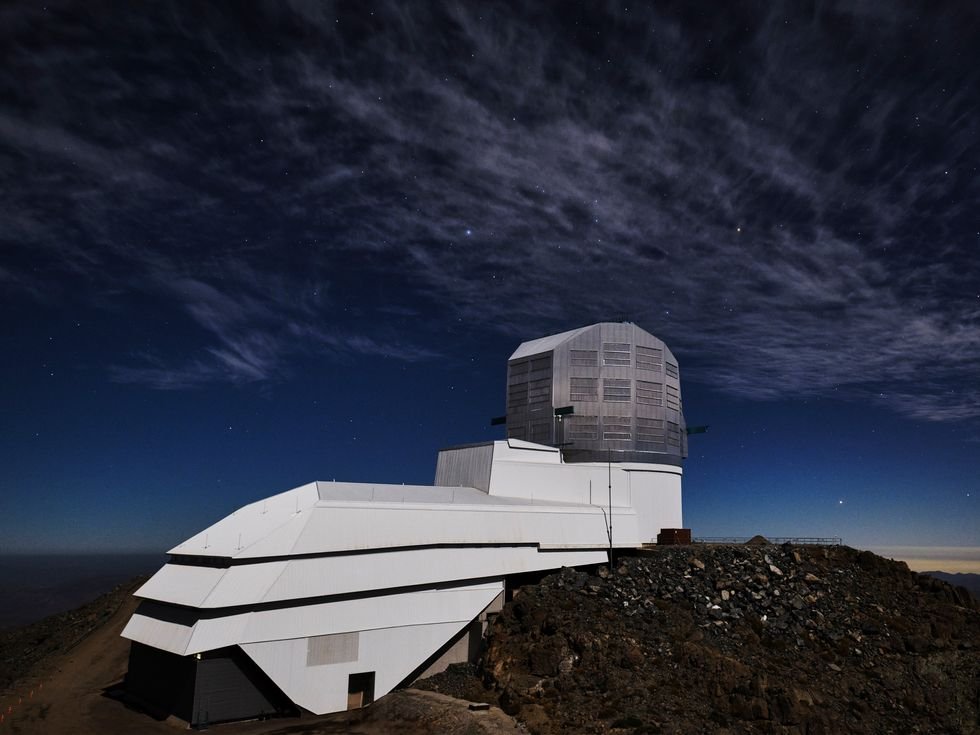

Stars begin to appear above, and O’Mullane and I pack up our cameras. It’s astronomical twilight, and after nearly three decades, Rubin is ready to embark on its mission.

As Rubin’s object catalog expands, astronomers can query it in various meaningful ways. Seeking all images of a specific sky region? No problem. Identifying galaxies of a particular shape? Somewhat more challenging but achievable. Searching for objects similar to others in some aspect? Time-consuming, yet feasible. Astronomers can even run personalized code on the raw data.

In 1995, the Hubble Space Telescope focused on an unremarkable segment of the sky for a total of six days. The resulting image, known as the Hubble Deep Field, unveiled approximately 3,000 distant galaxies within an area representing a mere one twenty-four-millionth of the sky. Observatories like Hubble, and now Rubin, reveal a sky brimming with so many objects that it becomes a challenge. As O’Mullane explains, “There’s almost nothing not touching something.”

One of Rubin’s primary challenges will be “deblending” — identifying and deciphering overlapping objects like stars and galaxies. This meticulous process involves analyzing images captured through various filters to estimate the composite brightness of each pixel from different sources.

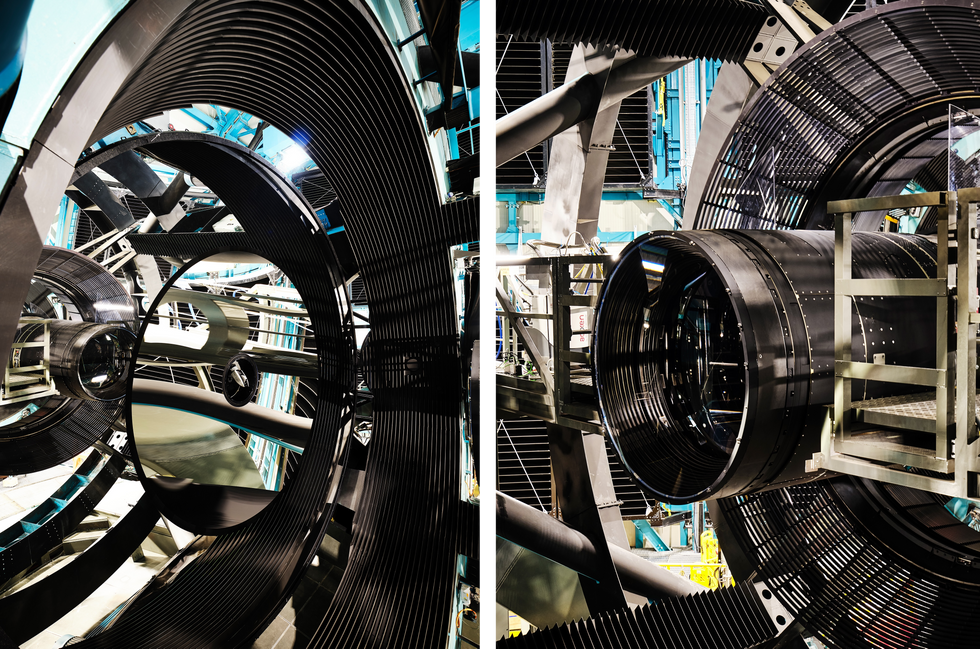

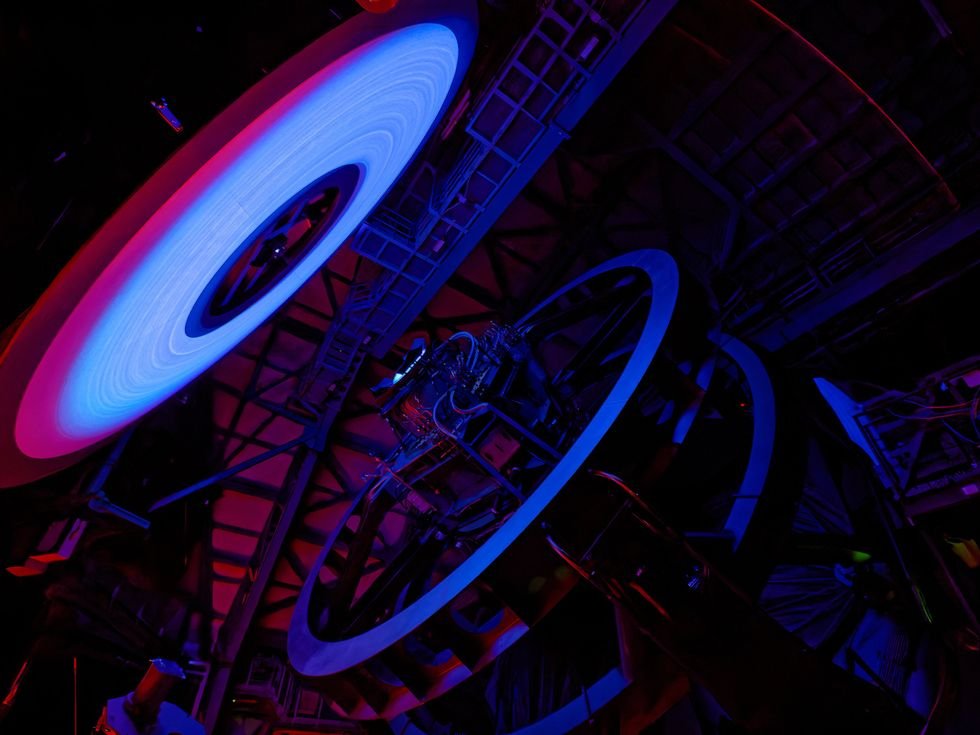

As my summit journey ends on April 14, just a day before the first photon, I reach out to some of the engineers and astronomers I met to follow up on the event. Guillem Megias Homar oversees the adaptive optics system, with 232 actuators to fine-tune the telescope’s mirrors for crystal-clear images. Currently pursuing his Ph.D., born a year after the Rubin project’s inception, the experience of the “first photon” resonates with him:

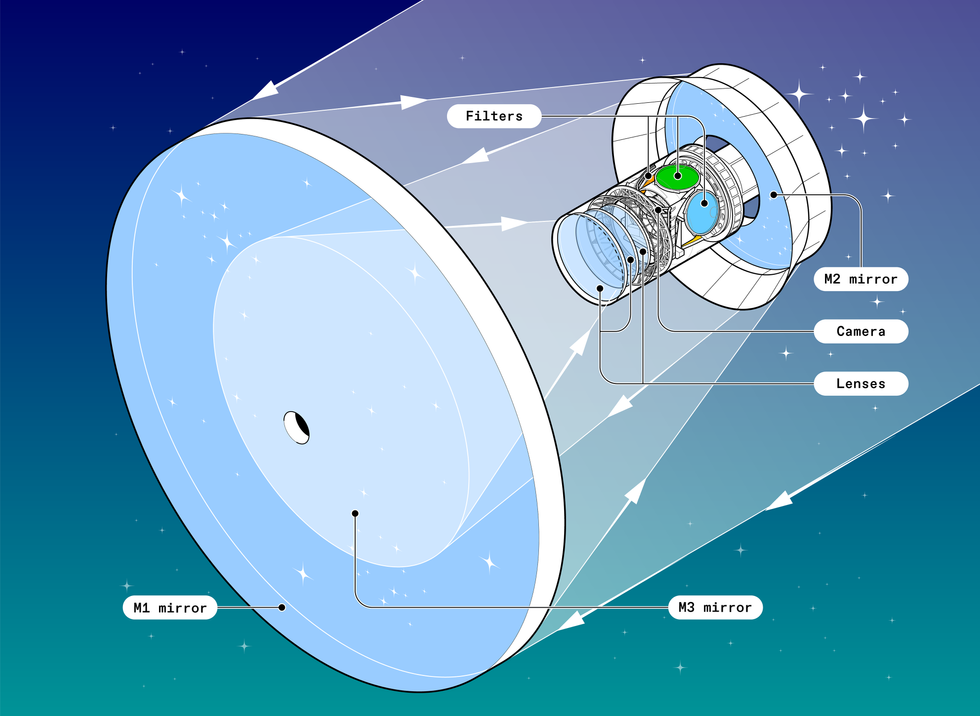

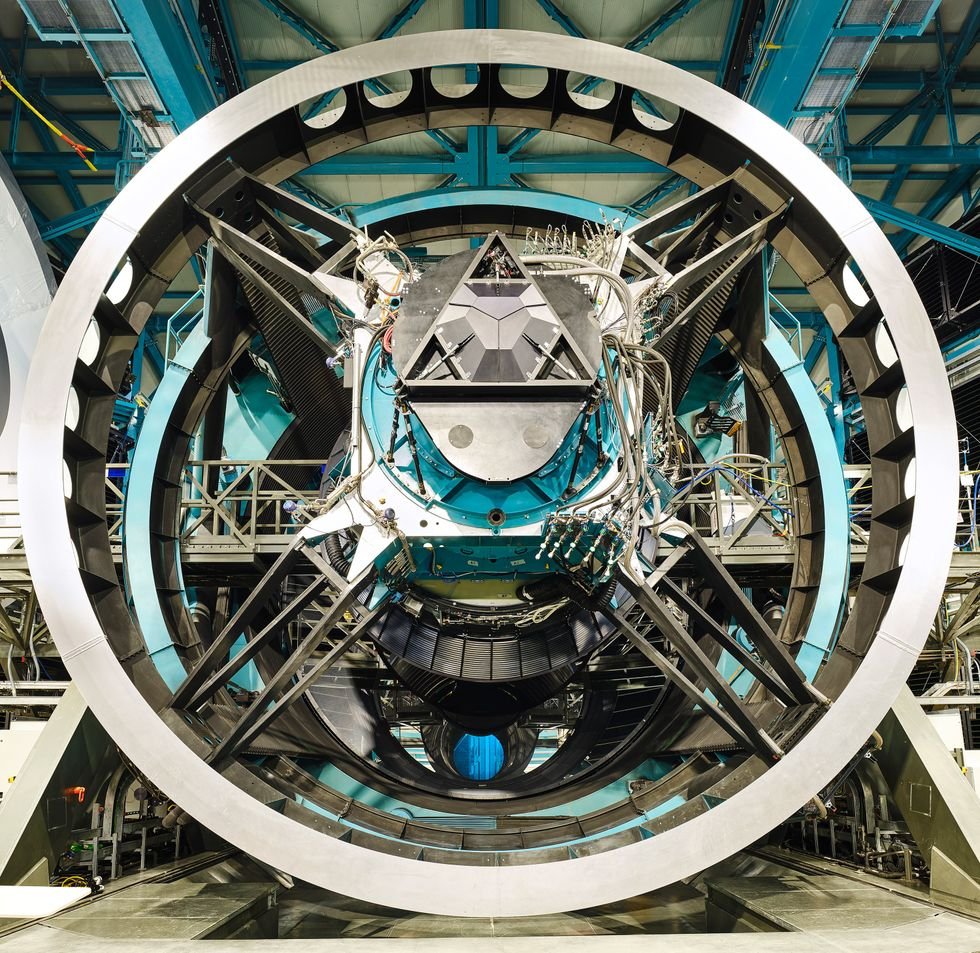

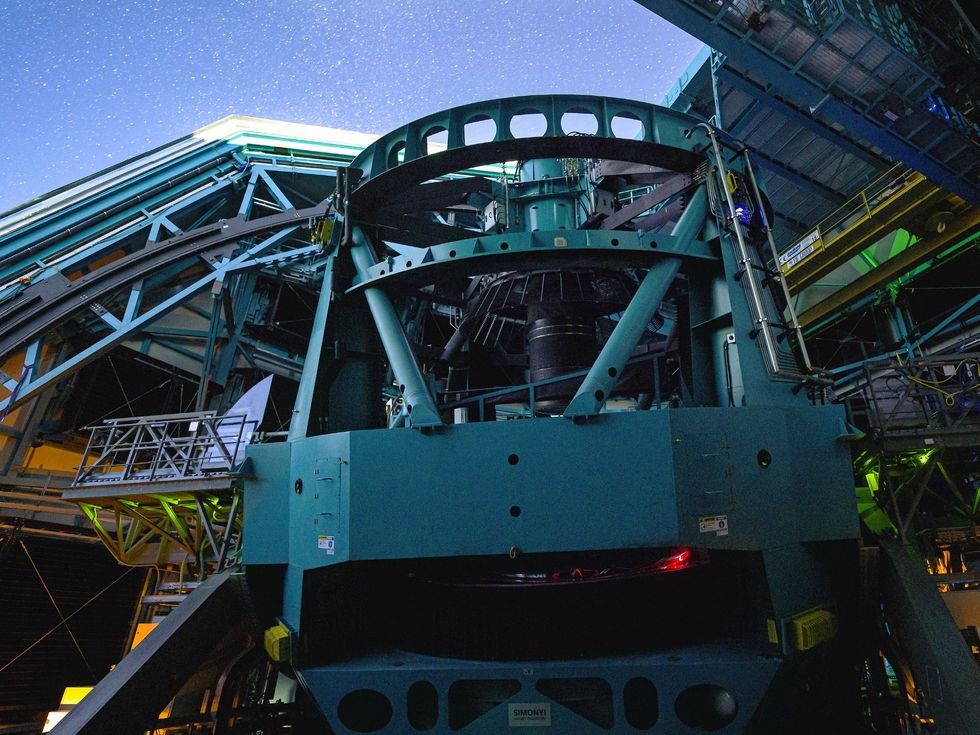

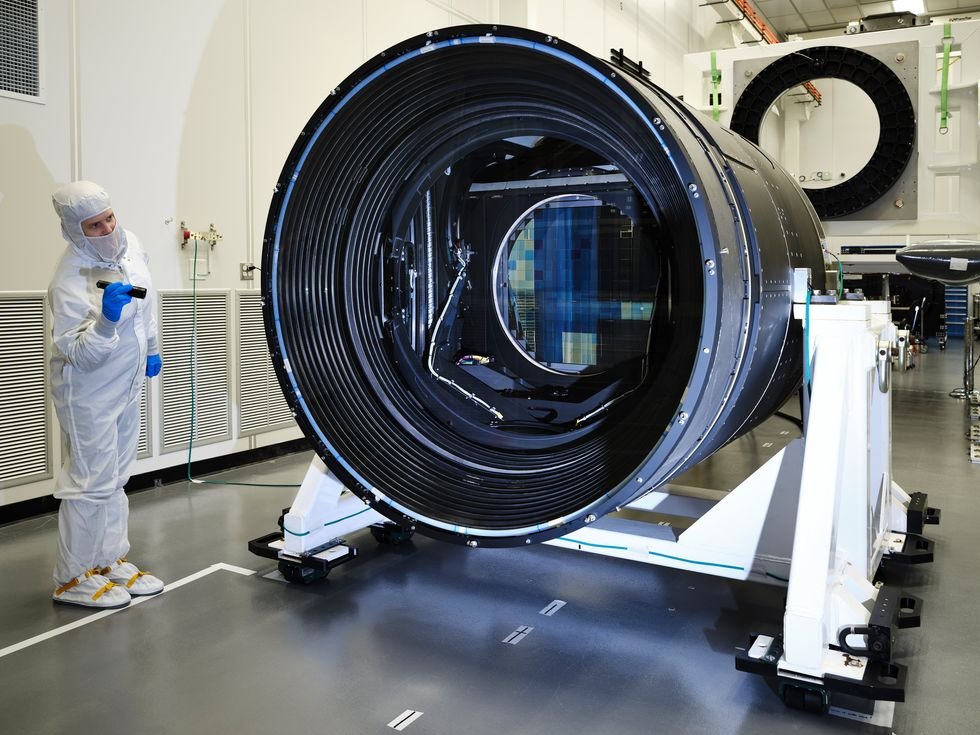

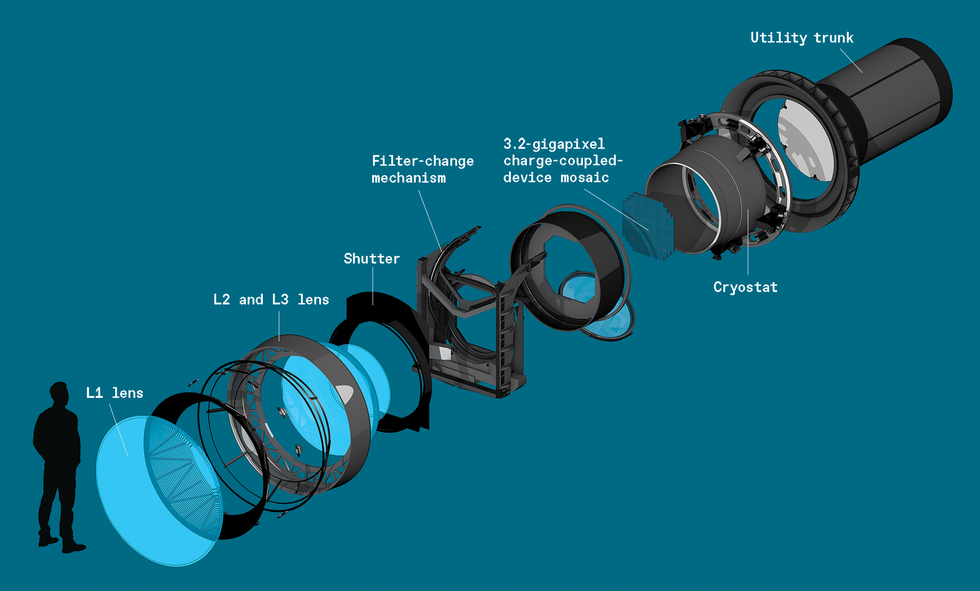

While many telescopes feature multiple instruments, Rubin integrates only one— the LSST camera, the largest of its kind.

Initially, Rubin won’t face this challenge. Visiting each location, the camera will capture a single 30-second exposure before moving on. With Rubin revisiting each spot every few days, subsequent exposures will be combined via a process known as coadding. In a coadded image, every pixel represents all data collected at that position from all prior exposures, resulting in a longer effective exposure duration. Although each individual image may capture only a few photons from a distant galaxy, accumulating these few photons over 825 images produces richer data. By the end of Rubin’s ten-year survey, coadding will generate detailed images resembling a standard Hubble image but spanning the entire southern sky. Specific regions, known as “deep drilling fields,” will receive more focus, accumulating an extensive collection of 23,000 images or more per field.

Every night, the telescope will snap a thousand images, one every 34 seconds. In three to four nights, it will cover the entire southern sky before starting over. Over the course of a decade, Rubin will rack up more than 2 million images, generate 500 petabytes of data, and survey every observable object at least 825 times. Alongside identifying around 6 million bodies in our solar system, 17 billion stars in our galaxy, and 20 billion galaxies in the universe, Rubin’s pace will explore time dimensions, tracking daily changes across the southern sky.

At SLAC, each image undergoes calibration, including the removal of satellite trails. While Rubin is expected to capture several satellites, their transient presence across images implies minimal impact on coadded data. Processed images are compared with baseline images, triggering alerts promptly, even as processing of the next image begins.

To us, with our limited vision and lifespans, Earth-bound and seemingly inert, the dynamism of our universe remains largely enigmatic. To our eyes, the night sky appears static and empty, though the reality is far from it.

Rubin emerges as an unmatched telescope, set to commence the 10-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST) across the southern sky with its wide field of view, incredible speed, and massive digital camera. The result will be a detailed account of the evolution of our solar system, galaxy, and universe over time, accompanied by petabytes of data representing numerous celestial objects never before seen.

Configured to function throughout the 10-year survey, the LSST camera boasts future-proof capabilities, with image quality maximizing the potential of the accompanying telescope.

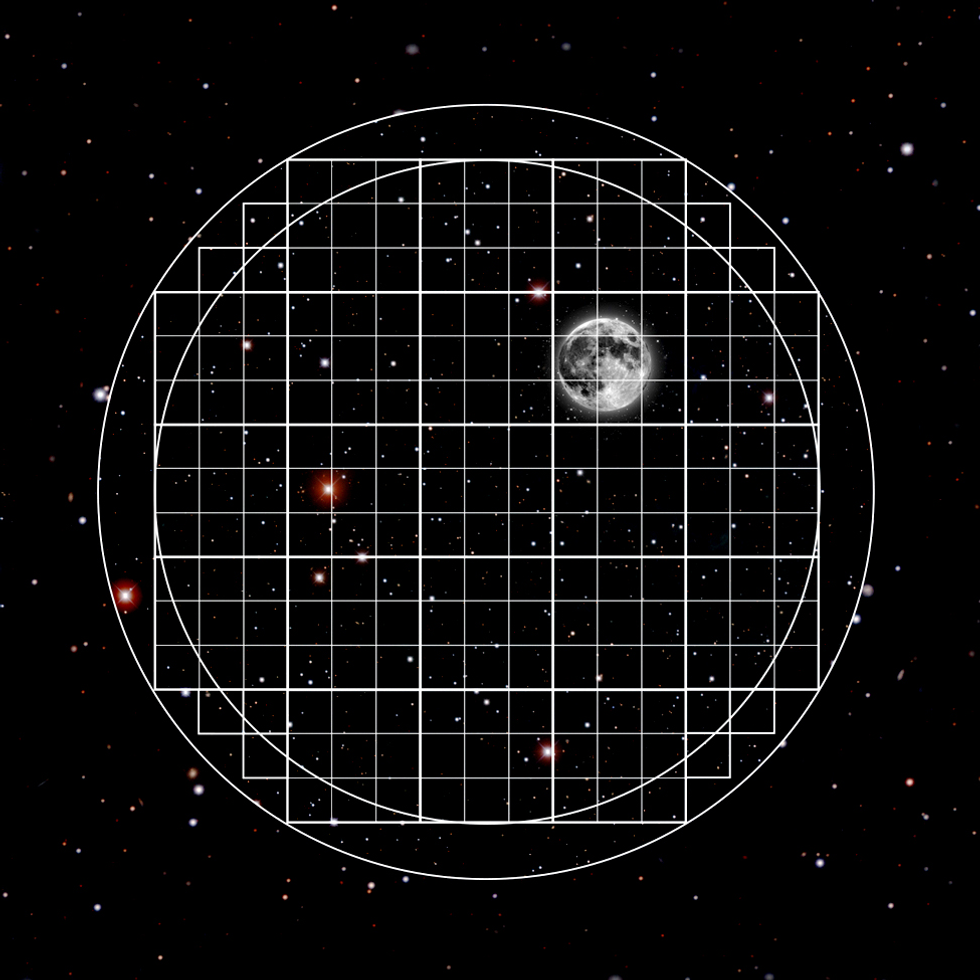

The LSST camera’s 189 CCDs combine to provide a 9.6-degree field of view, roughly 45 times larger than a full moon.